A New Form of Association for the Internet Generation — part 1

So far, the Internet has been very good at helping people do things together. But once it involves money, there is no good solution…

So far, the Internet has been very good at helping people do things together. But once it involves money, there is no good solution. Creating a new legal entity is too much overhead, too early. What if we could create a virtual entity that can collect money as easily as creating a Facebook Group?

No legal entity, no bank account, no budget

After selling Storify, I spent some time in Belgium to help the local startup community come up with a Startup Manifesto. The goal was to provide the Belgian government and society at large with recommendations to “make it suck less” for startups.

It was a grassroots effort that gathered 100+ contributions from the local community of entrepreneurs. At some point we decided to print stickers. But who would pay for them? Many were willing to donate money to help the movement, but how can we collect that money? Where?

It turns out that to create a bank account, you first need to create a legal entity. Too much overhead for such a grassroots movement. So we ended up using an existing organization (Startups.be) who paid the bill for us.

Fiscal Sponsorship

I got a similar situation with Tipbox, an Open Source project that I created with my friend Mark.

We received a $35k grant from the Knight Foundation, but we didn’t have a legal entity and a bank account to receive that donation. So we had to use their foundation as a Fiscal Sponsor. They kept the money on our behalf and we had to submit our bills and expenses. They would then process them and reimburse us. They are manually processing “hundred+ requests per week”.

There’s got to be a better way.

Chapters

I asked around to see if other people were facing similar situations. My friend Alaina Percival is the CEO of Women Who Code. It took her almost 2 years to get her 501(c)(3) status (a non-profit status in the US). Now, they have 50+ chapters around the world. Each of those chapters don’t have a legal entity on their own. As a result, they can’t raise money and they can’t have a budget. That’s a real limiting factor to scale the movement.

They work around this through the concept of Fiscal Sponsorship. Donors donate to the main organization online and specify the chapter they are supporting. The main organization keeps track of the budget for each chapter and processes their expenses, manually.

I also talked to Dries Buytaert, the founder of Drupal. They have hundreds of Drupal related meetups and conferences around the world that have spun up organically. Same deal. Most of those local groups don’t have a legal entity and are limited in what they can do.

Finally, I talked directly to meetup organizers, leaders of open source projects, sport clubs and other small associations. They either avoid money altogether and solely rely on individuals or sponsors to directly pay for their expenses, or they collect money on their personal PayPal account and take the burden to provide some level of visibility to the group.

There are plenty of situations like these where we should be able to quickly spawn a lightweight organization with a dedicated bank account for a side project or a group. But we don’t want to encumber ourselves with the creation of a legal entity.

If you recognize yourself in one of those situations — if you have problems collecting money and dispersing it for a side project or an association of any kind — please get in touch or share your story publicly with the #OpenCollective hashtag. That way we can all learn from the issues on the ground and contribute to the solutions.

Why existing legal entities don’t work anymore?

Before the Internet became a commodity, creating an organization required a lot of capital and planning (remember those business plans with a 5-year financial projection?). There wasn’t much room for uncertainty. Governments put in place a rigid framework to provide stability for companies to blossom. They needed to make sure that the companies with whom you may do business wouldn’t die the next day. And since they cannot have a controller in every business, they required each of them to send consolidated reports of their activities every quarter or every year, adding a fair amount of bureaucracy in the process.

Rigidity was a feature, today it’s a bug

Requiring all those small projects to create a legal entity as soon as they need a bank account is unnecessary overhead. When you don’t know yet if your project will succeed, how long it will last, or whether you would still be an active contributor a year from now, you don’t want to bind yourself to a rigid legal entity. You don’t need rigidity, you need flexibility.

Redefining the concept of association for the 21st century

Creating an association should be as easy as creating a Facebook Group. For most cases, we shouldn’t have to worry about creating and maintaining a legal entity. Yet those associations should be able to collect money and disperse it for their activities.

Instead of creating these associations using a 20th century framework* that assumes that the money collected goes into a blackbox and therefore requires reporting to avoid abuse, what if we could create new associations on a more open and transparent model, where the collected money wouldn’t go into a blackbox, where we wouldn’t need to file annual reports with consolidated numbers, and where corruption would be impossible by design?

* The equivalent in France of a 501(c)(3) is called “Association de loi de 1901”, it cannot be more clear about how outdated that framework is!

Why does it matter?

Movements like Women Who Code, new political parties like Podemos, new unions, citizen initatives to help refugees, etc. start and grow with bottom up initiatives; local groups who decide to do something in their city to contribute to a larger movement. If those groups can’t raise money locally, they can’t sustain themselves. Remember #OccupyWallStreet?

That’s why we need a new lightweight type of entity for our generation. We need to remove the friction that exists today to collect money for an association of people. So that we can do more, together.

That’s how we will empower people in a bottom-up fashion to fuel those movements and operate the necessary changes to improve our societies all around the world.

How can we do that?

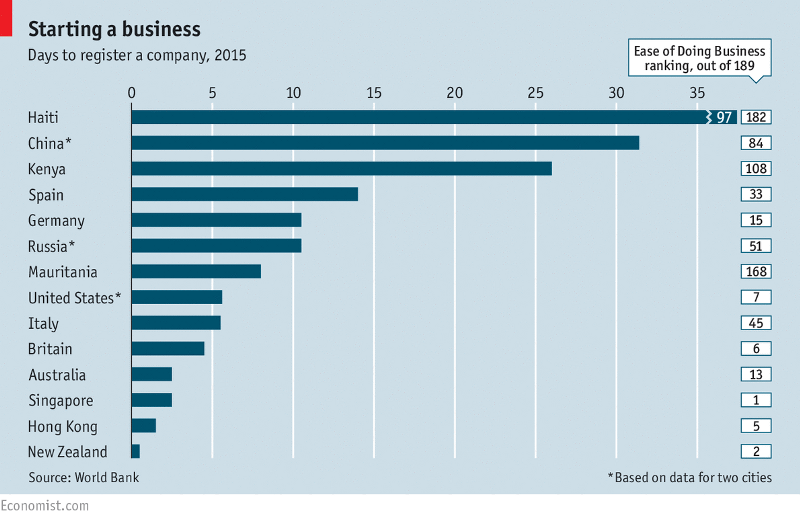

We can lobby our governments to update the legal framework. That’s what we tried to do with the Startup Manifesto in Belgium (the number one recommendation to the government was the creation of a new legal entity “Startup, Inc.”). But it will take years, if it ever happens. Plus, the problem is not limited to one country. It’s a global issue.

If you can’t fix a layer down the stack, abstract it and move on

We have seen that movie before. We couldn’t fix Microsoft Windows, so we built web browsers on top of it. They allowed anyone to innovate by building new web services without having to worry about the underlying complexity (and bugs) of the operating system.

Governments are also operating systems. Instead of managing hardware, interruptions and other bits, they manage a territory, natural resources and citizens. It’s a geographically constrained operating system engineered hundreds of years ago, way before people could communicate in real time across the globe.

All around the world, those operating systems are overdue for an upgrade. So what’s the equivalent of the browser for our outdated and geographically constrained operating systems?

The emergence of cross-governments global services

Today, it doesn’t matter if you have an apartment in London and one in San Francisco where local regulations are different. You have one single interface to manage them: AirBnB. They even withhold taxes for you.

Same with Uber. Whether you are in Beijing, Cape Town or San Francisco, the same app with the same interface will bring you a car and drive you where you need to be. The local currency might be different, the local rules might be different, but the experience for you (as well as for the driver) is shielded from all that complexity.

Through those new global services, we see emerging a new layer on top of local governments. This layer provides a unified and streamlined interface that empowers people to focus on what they need to do.

Creating an organization is another of those situations where local governments expose a lot of complexity to the end user. We need to abstract that complexity so that people can focus on the primary goal of their organization.

In part 2 next week (next year!), we will explore how we could build such a new layer to empower people to create associations with much less friction. Stay tuned. UPDATE: Here is part 2.

Thanks to Aseem Sood, pia mancini, Burt Herman and Lionel Dricot for having read and contributed to drafts of this post (and Pierre Wolff who read the very first version back in September! Note to myself: don’t wait 3 months before publishing a blog post)