Open-source intelligence for investigating war crimes

Emmi Bevensee is a data scientist and researcher of complexity, hate, the far-right, and disinformation, originally from the US and now based in NZ. They created Social Media Analysis Toolkit (SMAT) to facilitate activists, journalists, researchers, and other social good organizations to analyze and visualize misinformation, disinformation, and harmful online trends.

Emmi’s journey of researching disinformation and white supremacy started around 2015, working on the Syrian border.

“I became interested in the nexus of Russian chauvinistic propaganda networks and white supremacy in the West. I was really disturbed by far-right trends, and how quickly intense violent groups mobilize. I started noticing these websites; at the time, 8chan was the most infamous. Now there are a lot more, using different technologies that are more resilient”.

The idea for SMAT was born from Emmi’s research of these ‘free speech’ forums, known for hosting white supremacists, and building tools to analyze them. For a while, academic journals would decline to publish scholarly papers about it, considering them ‘too niche’. But in recent times, the importance of this field has become ever more apparent.

SMAT is a set of open tools for analyzing content from websites that are infamous for their connection to real-world violence, which usually go unmoderated and cause the spread of hatred and dangerous ideas. It’s built and used by a community of researchers, hackers, and activists, many remaining anonymous because of threats to their safety.

SMAT offers free public tools and a free public API researchers can request data through. It also has paid services and tools used by researchers and journalists to tell important stories. All kinds of investigations have been done with the help of this technology.

The latest SMAT story concerns the Bucha massacre, one of the most highlighted cases in the ongoing Ukrainian-Russian war.

Bucha was a nice neighborhood in the Kyiv suburbs, home to many families and younger people, including displaced persons from Donbas following the outbreak of war there in 2014. In the first days of the current war, Bucha was occupied and became the epicenter of the conflict. The city underwent vast destruction; a mass grave was discovered next to a church; rapes, tortures, and executions of civilians were reported. Many atrocities were revealed after the military retreated from the region.

The SMAT team decided to use their tools to uncover the truth, investigating who was responsible for committing these war crimes. They started crawling hundreds of Telegram channels related to the conflict, both Ukrainian and Russian. A small team of people familiar with the situation labeled content by type, then tools were created for investigators to search through the media. A lot of weird, misleading, and confusing things were found.

“SMAT’s data is supposed to be messy. We do our best to label and provide indicators, but it’s raw data. It contains the entirety of the information of the online landscape, so there is going to be all kinds of manipulation. We say upfront: do not take this information at face value”.

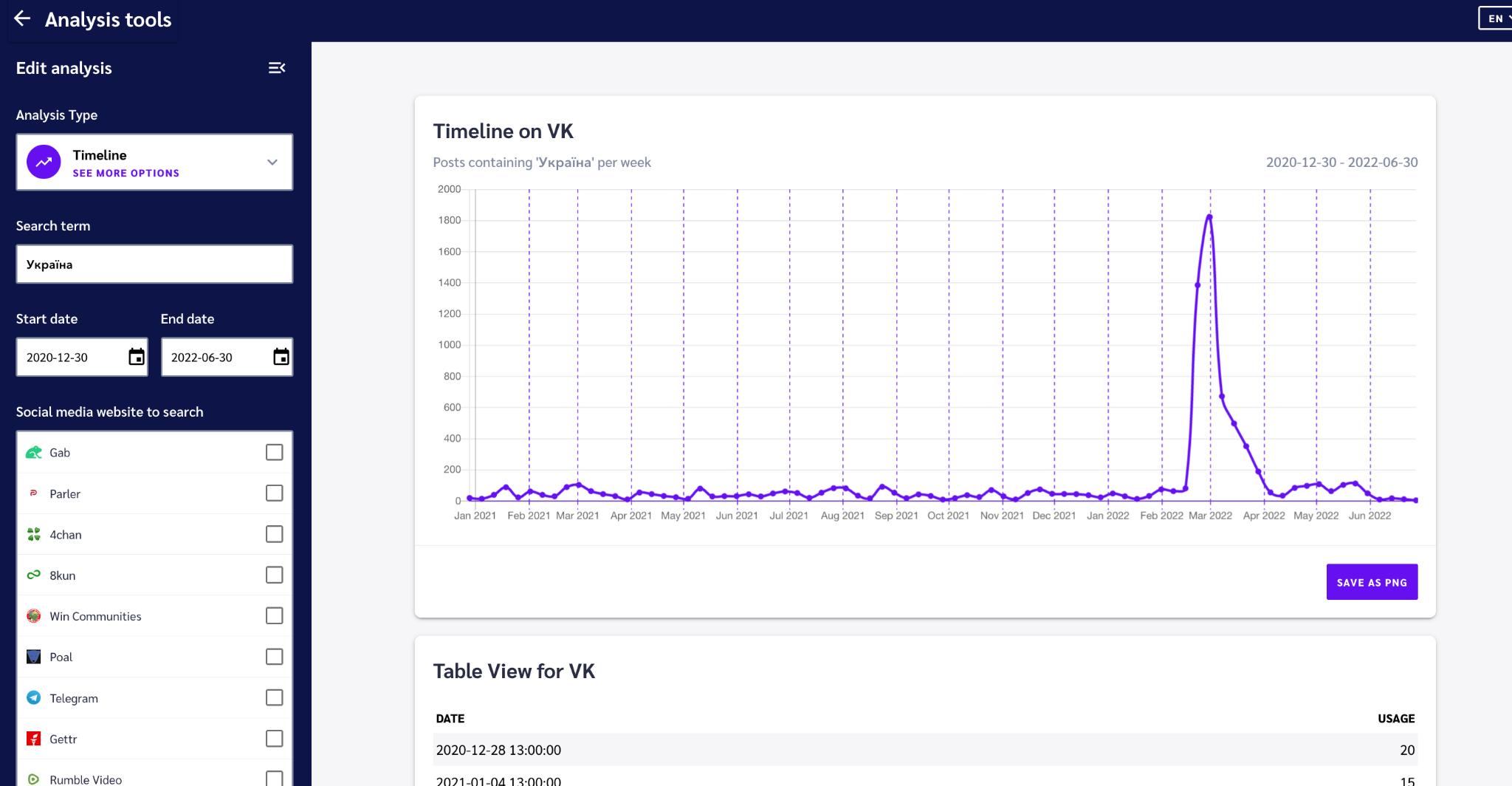

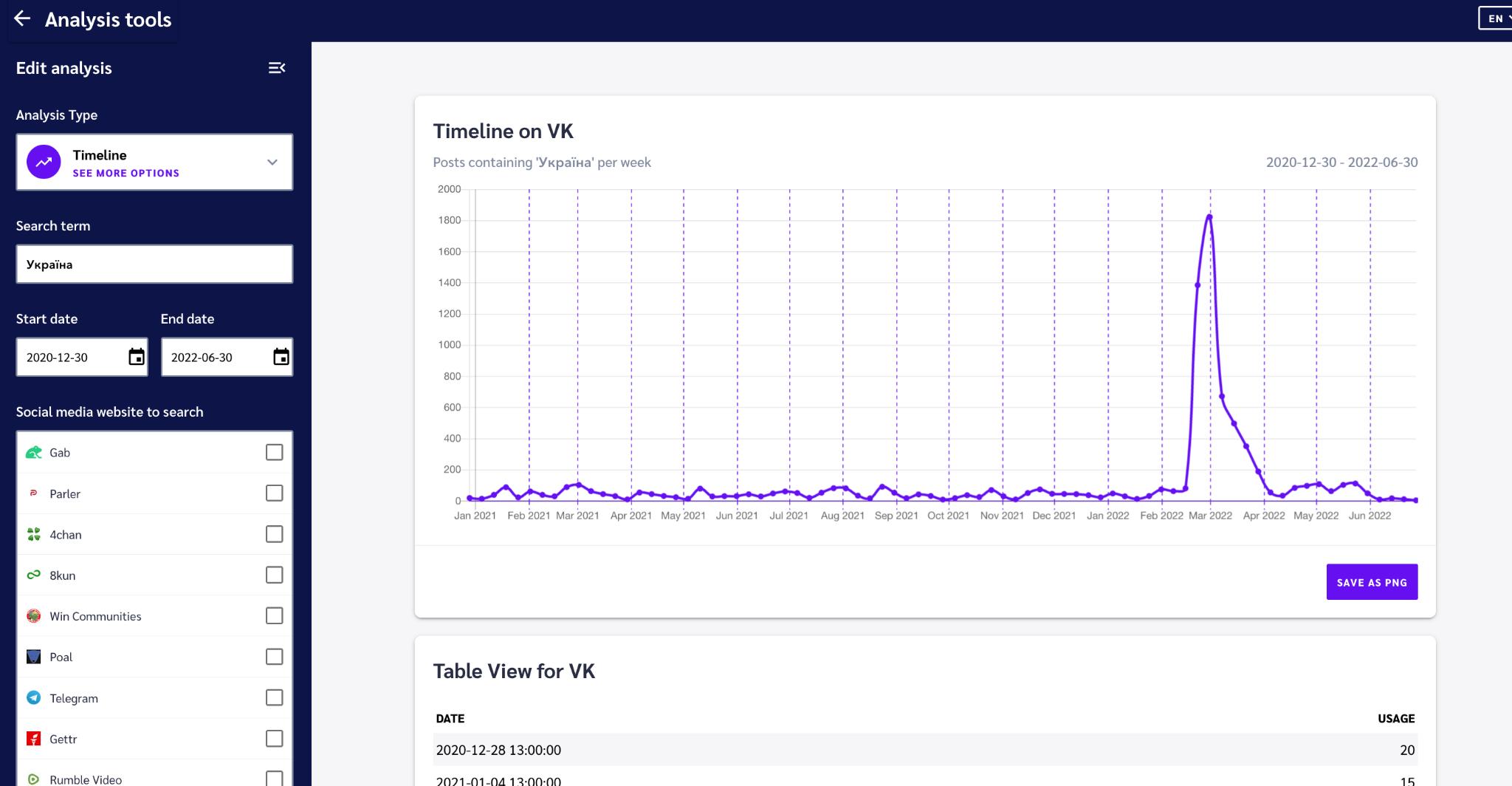

The project then began crawling VK groups related to the conflict. White supremacist groups, including those in the US, use VK because it is perceived as being less moderated. As the most popular social network in Russia, many soldiers have VK accounts. After a list of the names and passports of Russian troops in Bucha was released, SMAT started matching the data with VK profiles.

One obstacle was the similarity of names, requiring them to cross-reference different types of information. The team began cooperating with invader.info, a project launched by a Ukrainian data scientist who was looking at the same problem in alternative ways, including facial recognition. Combining automated methods with intensive manual verification, many of the Russian soldiers’ profiles were identified.

After a series of Bellingcat investigations (especially the exposure of FSB attempts to assassinate Navalny with novichok poison), the Kremlin made it illegal for soldiers to post on social media and tortured data brokers. Despite the ban, the SMAT team found recently active soldier profiles on VK, some who had even helpfully put the number of their military unit in their bio. They crawled the data and archived proof that content was there before the war, to show these weren’t cases of framing after the atrocities. In the end, they positively identified 9 of the ‘Despicable 10’ perpetrators.

The question now is, will the war criminals be brought to justice?

“I’m not going to lie: a lot of the processes that exist are pretty toothless. ICC criminal cases are regularly flouted. Certainly, Russia won’t extradite anyone. The future of this investigation depends on the future of Russia. Linking VK photos and biographic data to military positions, then connecting this identity to CCTV footage, is strong court-admissible evidence. The practical short-term impact is that the criminals can’t travel outside of Russia. Countries like Belgium can prosecute international crimes against humanity, and they’ve had court cases against Russian separatists who attacked MH17 [causing the airplane to crash]. One of Assad’s torturers got spotted in Germany by a victim. They launched an investigation, including open-source data, and he was formally charged with war crimes in Germany. That’s not common, and it’s not enough, but it’s meaningful nonetheless and undermines Russian propaganda whitewashing their crimes”.

Governmental intelligence agencies work in private and gather data in a centralized way, while open-source intelligence has everyone working together to create a decentralized network that responds to ongoing threats. Distributed, networked, and open approaches to intelligence work will be critical going forward.

“The future of massively confusing ongoing disasters is extremely far beyond the capacity of any centralized organization to process, including governments. It’s too much data. Some organizations do secretive investigations, while we are open-source practitioners working publicly. We say. 'This is what we found; this is how we found it.' You can criticize our methods; you can challenge the findings. Or you can use them as leads to keep digging.”

This work can be very toxic, requiring high mental resilience and tools for coping with negativity. Vicarious traumatization describes how people who work with data about severe trauma commonly develop PTSD symptoms themselves. In part, SMAT was created to avoid that, by automating the soul-destroying work of sorting through thousands of violent posts. For Emmi, self-care is a form of activism, too. SMAT seeks to build a supportive community, a space where people doing this challenging work can be open and understand each other.

“People I know have been traumatized by resisting white supremacists. They’ve been shot, stabbed, or sent to prison. And everything is just getting more intense with time. This work has had a big impact on my worldview. It’s hard to see the world as being on a good, safe path. But it also makes me care a lot about building a world worth living in. Against the odds, there’s a lot worthy of love and protection.”

Next up, SMAT is attempting to building partnerships, such as with war crimes prosecutors and archivists, and researching new data sets, like content from the Truth Social. They are seeking donations through Open Collective, and investment, to scale their efforts to meet the size of these world-changing problems.